« C’est mon rêve, aller aux Etats-Unis. Vous savez pourquoi ? »

« Le nouveau président ? »

« No, je m’en fous. Pour Elvis. Je veux aller au Memphis pour voir Elvis. »

This employee at Père Lachaise began by letting us know that the cemetery was about to close. When he found out we were American, however, he asked us all about life in Elvis’s country.

« Je suis de Californie. »

« Ah bon ? C’est près de Memphis? »

A strange preoccupation for someone who spends every day at a cemetery where most of the world’s significant non-Elvis figures are buried, but that afternoon we came to realize that the popular conception of the afterlife does not tolerate the meddling of rational thought.

The most popular memorial style in Père Lachaise is the most ornate. Houses sized down to a third their usual size, perhaps with the kind of proportions you’d see in Disney’s Toontown, these gorgeous constructions make of death a stately affair.

Their grandeur called to my mind vanitas paintings, a Northern European genre popular in the 17th century for allegorically portraying inevitable mortality and the ephemerality of worldly possessions. “Vanity of vanities; all is vanity.”

Père Lachaise is not the place for these austere philosophical musings. Any regret of worldly fixations becomes hushed in the face of these edifices. In effect they recreate what must have been the lavish homes these people enjoyed during their lives; simple mortality cannot deprive them of the lifestyle to which they have become accustomed.

However, the passing centuries add another layer to these three-dimensional portraits. Kai mentioned the Doornik memorials, which have assumed a meaning that their architect and inhabitants surely did not intend. If one had an immature mind and watched too much television, one might remember them this way:

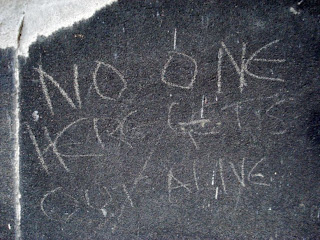

That would not be the first imposition of juvenile humor onto Père Lachaise. One intrepid Jim Morrison fan etched the following into the side of an unrelated house-shaped grave:

Death is a philosophically contentious matter, and cemeteries tend to become battlegrounds for different ideologies. Père Lachaise is no exception. The grand dignity of the graves themselves sets them in opposition to more severe views of death, provokes a contrary irreverence in some, creates a peaceful, not at all sad environment for others, and generally clashes with the matter-of-fact steps of tourists. A trip to the cemetery, therefore, is not only a rich aesthetic experience, but also an opportunity to observe one’s own thought in action.

No comments:

Post a Comment